By Year-End We Will Have Built 100+ Agents Across Three Industries — Here Are the Takeaways

I. INTRO

The AI and agent space moves fast, and the noise makes it hard to know what’s real. In many industry conversations, you can sense people trying to navigate the mix of excitement and uncertainty—sorting out what’s signal, what’s noise, and what actually fits their domain.

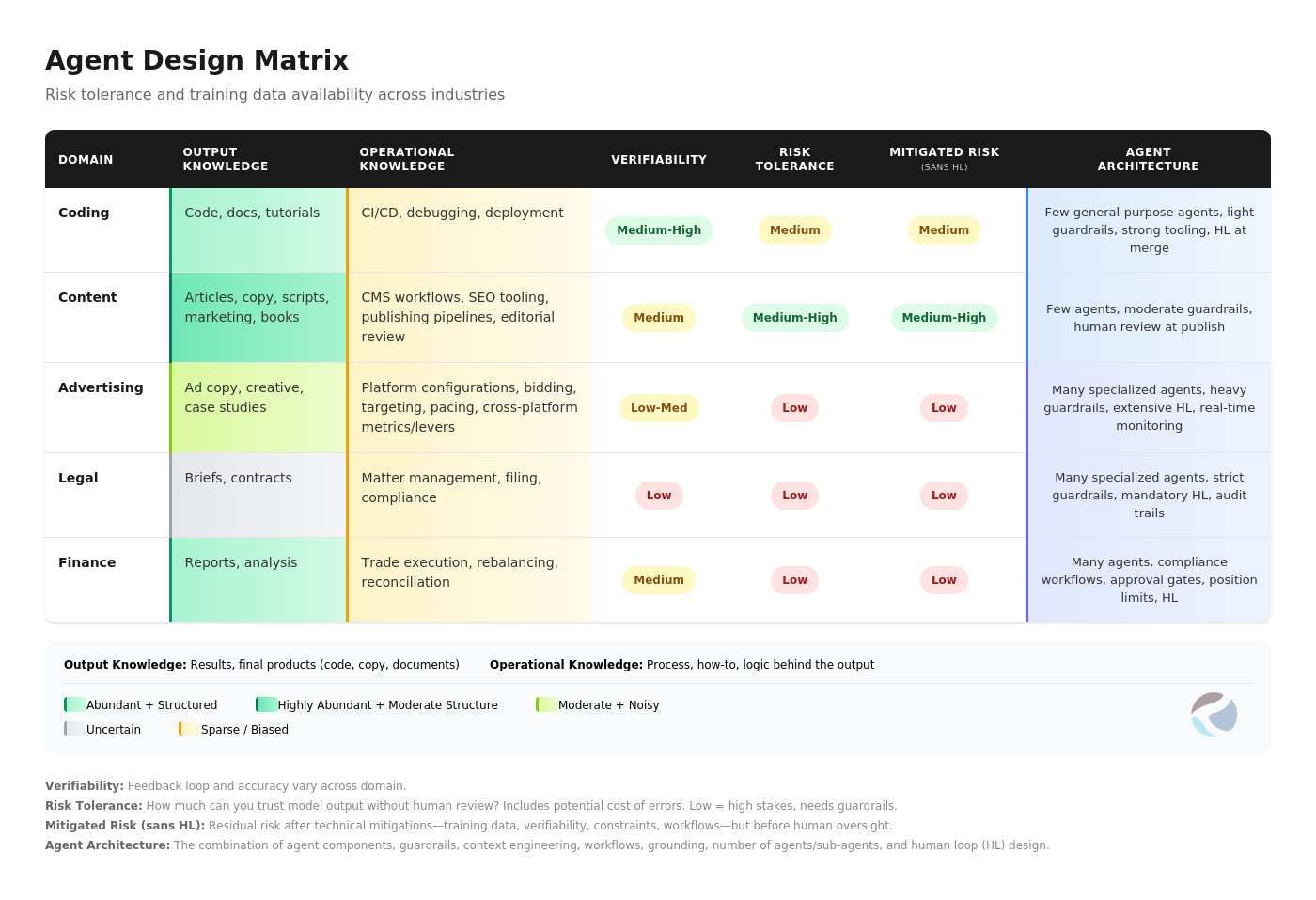

Building agents across industries forced us to view agents and architecture through a different lens. Most visible wins and quality research comes from coding and content-creation agents—domains where models perform best, risk tolerance is higher or validation is easier.

The main takeaway: those lessons don’t translate across industries and specialties. Every domain has its own constraints, risk profile, and data reality.

Here’s what we’ll cover:

1. The core building blocks (components) required for agent and multi-agent ecosystems ( Section II - III )

2. Factors that govern how much of each component you need to create or refine agents ( Section IV )

3. Common points of confusion around AI, Agents, and LLMs ( Section V )

A few patterns emerged along the way:

· Agent Architectures don’t always generalize. Coding or content-creation agents work one way; advertising operation agents require a fundamentally different architecture.

· The component mix varies widely. Traditional AI/ML, workflows, LLMs, context/memory, human-in-the-loop (HL), reasoning—every domain, agent, tasks benefits from a different blend.

· Model training data, industry risk tolerance and mitigation of risks. This directly impacts agent performance and design complexity. Various specialized domains have the same issue of poor training data and model performance given the sparse, biased, unstructured or proprietary nature of the data in that space.

· Architecture complexity follows risk tolerance. Some domains are able to succeed with one or two well-designed agents. Others need 10, 20, or many more specialized agents—not because they’re over-engineered, but because the domain demands it.

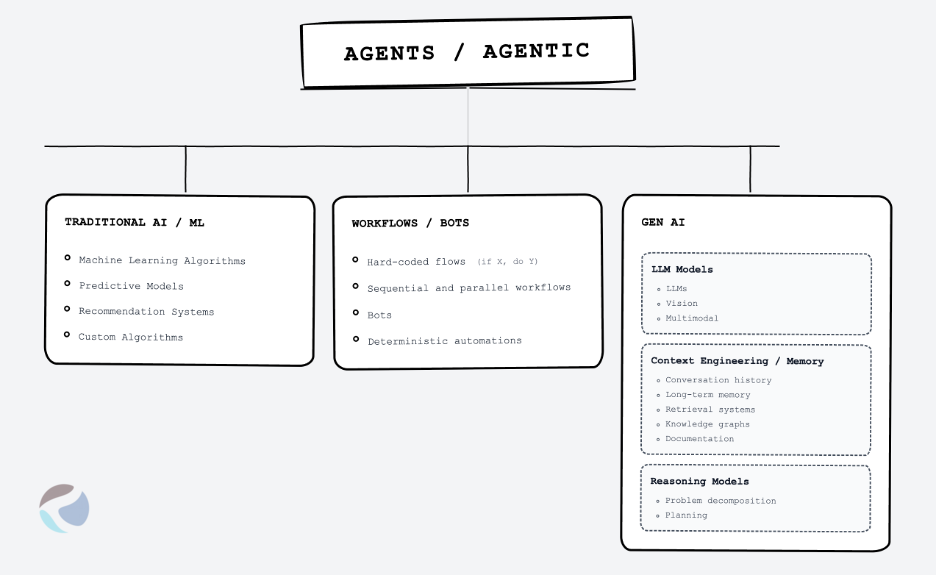

II. The Three Major Components (Agents/Agentic)

These are not agents on their own. (Visual chart above)

Component 1: Traditional AI / ML (Pre–Gen AI)

This is everything that existed before the era of LLMs, and it still matters just as much or more depending on the build.

Includes:

• Machine Learning algorithms (regression, classifiers, clustering, etc.)

• Predictive models

• Recommendation systems

• Custom algorithms

• Statistical models

• Domain-specific ML pipelines

Insight: Not every company or platform that “uses AI” is in the agent or agentic space. These systems are deterministic ML pipelines or analytic engines. Combining these methodologies and interposing them into agent or multi-agent architecture is where we stand to extract even more value. For example, the ability to take action on insights/intelligence dynamically, at higher frequency, and with HL guiding direction.

Value emerges when deterministic models, humans, and agents operate together—intelligence informing action, and humans guiding direction.

Component 2: Workflows / Bots / Automations

This is not “AI/Agents” in the modern sense; it’s logic. An important part of agents, but the level depends on the task, domain, etc.

Includes:

• Hard-coded flows (”if X, do Y”)

• Sequential workflows

• Parallel task runners

• Bots and rule-based automations

• Multi-step deterministic procedures

• Robotic Process Automation (RPA)

Insight: These can look like “agents” but they’re rigid. They don’t generalize, can’t improvise, and don’t “think”. They execute instructions and have to be manually shaped whenever customization or any strategic changes are demanded. Operations that require flexibility benefit from well-designed agents/agentic architecture layered on top of workflows.

Component 3: Gen AI (with sub-buckets)

This is the most important component of agents or agentic systems. Meaning at a minimum it must have one of the below piped in. But it makes more sense to break it down to subcategories given its rapidly evolving complexity.

Sub-Bucket 3A: Foundation Models

Includes:

• LLMs (GPT, Claude, Gemini, Llama, Open-source models, etc.)

• Vision / Multimodal models

• RLHF / Instruction-tuned variants

Data Insight:

These LLM models listed above are generally strong in coding, content-creation, or a few other general domains. However, performance degrades when training data is sparse, biased, unstructured or proprietary – leading to incorrect and overconfident outputs where real operational data isn’t publicly available.

Sub-Bucket 3B: Context Engineering / Memory Systems

LLMs have no native memory and recollection—each request starts fresh, with no knowledge of prior interactions. Context is an engineering layer, not part of the model. This is also critical to the human-in-the-loop design and UX choices.

Includes:

• Conversation history

• Long-term memory

• RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation)

• Knowledge graphs

• Document ingestion

• Summaries / compression / distillation pipelines

• Fine-grained context injection

• Domain knowledge bases

• Structured memory orchestration

Insight: Memory systems dramatically shape agent behavior. Two agents using the same model + same workflow with two different memory stacks behave like different agents.

Sub-Bucket 3C: Reasoning Layers / Reasoning Frameworks

This is the “thinking” layer—how you structure a model’s problem-solving approach, distinct from the model outputs.

Includes:

• Chain-of-thought prompting

• Self-reflection loops

• Task decomposition patterns

• Planning scaffolds

• Multi-step reasoning architectures

• “Thinking” workflows the model generates dynamically

Distinctions:

• Workflows → fixed logic

• Reasoning → dynamic, model-generated logic

Insight: The need for reasoning varies by domain. Reasoning enables adaptive workflows—useful in some creative, coding or variable tasks. However, reasoning doesn’t fix weak training data and performance. An LLM can “reason” its way into the wrong approach and/or outputs if it lacks foundational domain knowledge.

Reasoning doesn’t fix weak training data—it can just as easily lead you to the wrong answer with 100% confidence and sound logic.

III. Agents = The Combination of All Buckets

Agents aren’t their own bucket. An agent is the fusion of:

• A model (3A)

• Context Engineering & Human-in-Loop (3B)

• Reasoning (3C)

• Workflows (Bucket 2)

• Optional ML / analytics (Bucket 1)

• Domain-specific instructions

• State

• Tools

The challenge is that specialized domains require different fusions of these components.

Design Insight:

• Coding or Content Creation = can rely more heavily on training data + reasoning + tools; smaller number of agents and fewer guardrails.

• Advertising Ops = weak training data, high noise, subjective tasks → requires more memory, more scaffolding, more workflows, more narrow specialized agents (separating toolsets), more data constraints.

IV. Agent Architecture Decisions

Training Data is the critical point here:

• Coding or Content creation → huge training data sets → very strong performance

• Advertising → small training corpus → poor baseline performance

• Legal, finance, healthcare, taxes → also sparse or unstructured data → lower “out-of-the-box” quality

Additional Insight: LLMs are always behind the present (6-12+ month lag). Without retrieval, grounding, fine-tuning, or other augmentations – agents perform poorly.

Risk tolerance explains architecture. Domains with lower risk tolerance and low mitigated risk require more agents, more constraints, more workflows, and more human checkpoints. This isn’t over-engineering and design—it’s responsible engineering.

V. The Source of Industry Confusion

The agent discourse is dominated by coding and content-creation (adjacent) use cases—domains where models perform better out of the box. This creates reasonable but misleading intuitions:

1. Success in coding or content-creation agents suggests similar architectures should work elsewhere.

2. The similarities or distinctions between Agents, Agentic workflows, traditional AI/ML, reasoning, context engineering, Gen AI models isn’t obvious from the outside.

3. Training data bias is crucial for architecture and the gap is likely not closing anytime soon

4. Multi-agent design looks like over-engineering but it’s a result of complexity and risk tolerance in specialized industries.

VI. Applying the Framework: Advertising as an Example

Why advertising operations requires more agents:

• Sparse operational training data — Models may have exposure to ad content, use cases, blogs, platform documentation but not the execution nuances, strategy briefs, platform configurations, or performance data that made them work

• Biased platform knowledge — Documentation steers toward platform business revenue. Sometimes that coincides with client outcomes but generally you need deep domain expertise to understand the best operational approaches.

• Low verifiability — Success is lagging, attribution is murky, platforms are opaque

• High risk tolerance required — Real dollars at stake, mistakes compound, hard to reverse mid-flight

• Deeply contextual — Brand, vertical, budget, channel, timing all affect what “correct” means

This demands more memory, more scaffolds, more workflow constraints, more specialized agents, and more human-in-the-loop checkpoints.

But the real unlock isn’t just automation—it’s closing resource-prohibitive gaps.

Experienced practitioners have always known what should be done: more granular bid adjustments, faster optimization cycles, real-time cross-platform rebalancing, multivariate testing at scale. These weren’t impossible—they were not worth the headcount, time, or risk given human constraints.

Agents change that calculus. They enable:

• Tactics that “weren’t worth an analyst’s time”

• Complexity that couldn’t be managed manually at scale

• Testing velocity that wasn’t operationally feasible

• Execution at a granularity that would require 10x the team

The practitioners who understand these gaps—not just the operations, but where the operations fall short due to resource constraints—are best positioned to help design and/or fine-tune multi-agent architecture that unlocks real value.